Blog

Capital Punishment Legislation in North Carolina: A Tale of Two Moratoriums

2009 picture of the Sojourners for Abolition and Reconciliation marching against the death penalty. Credit: Photographer: Anthony Shepherd

Capital Punishment Legislation in North Carolina: A Tale of Two MoratoriumsBy Amani Carson and Nivedha Ram

In 1972, the Supreme Court ruled on Furman v. Georgia that states’ indiscriminate and inconsistent applications of capital punishment were in violation of both the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution.1 This ruling began a national moratorium. Several states, including North Carolina, responded by revising their capital punishment protocols to satisfy the court’s concerns.

According to legal scholar Cynthia Adcock, North Carolina implemented one of the harshest, most pitiless death penalty laws in the nation – imposing a mandatory death sentence on anyone convicted of first-degree homicide with aggravating circumstances. It only took the state two years to repopulate the cells that had been emptied following the Furman verdict. Between 1974 and 1976, the state added 120 inmates to death row.2 In Woodson v. NorthCarolina (1976), the Supreme Court declared North Carolina’s mandatory capital punishment law unconstitutional. Once again, North Carolina lawmakers revised the state’s approach to first-degree murders with aggravating factors and created a two-part process by dividing the trial into a conviction and sentencing phase.3

Since 1977, North Carolina has acquitted, commuted the sentences of, or resentenced 71% of death row inmates.4 In 2001, North Carolina became the last state to grant its district attorneys discretion in determining the cases for which they would pursue capital punishment. Following this legislation, the state’s rate of capital sentences declined by 80%. Even after the nation determined the constitutionality of capital sentencing, the death penalty remained acontentious political issue, soon to be complicated by a debate over the constitutionality of lethal injection.

Constitutional objections to lethal injection led to a de facto moratorium in 2007. Thismoratorium continues as of this writing in late 2015. Among the interrelated factors that led tothis is that death row inmates across North Carolina began to raise objections to their sentencesbased on the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment, arguing thatthe execution protocol permitted administration of drugs in a way that could cause intense pain.Specifically, Willie Brown fought for a stay of execution arguing that he would be conscious during the procedure.5

Additionally, the North Carolina Medical Board declared in 2007 that physicianparticipation in executions violated the Hippocratic Oath.6 The oath conflicted with prisoners’ rights to humane executions, presumably made so because of the presence of trained medicalprofessionals. Meanwhile, Willie Brown’s effort at a stay failed, and Administrative Judge FredMorrison ruled that North Carolina prison officials failed to follow their promise to have a doctorpresent to monitor Brown’s vitals during his execution.7 In response to this failure to followexecution protocol, North Carolina set out to revise it. However, this led to a civil suit by deathrow inmates because it was undertaken in a private meeting, which did not follow theAdministrative Procedures Act. Due to this cascade of legal complications with lethal injection, executions could not proceed.8

Willie Brown, who before his execution said he “feels like he’s been an experiment”

In 2009, the North Carolina state legislature passed the Racial Justice Act to address racial inequities in death sentencing; it allowed condemned prisoners to seek a commutation ifthey could prove that race was a significant factor in imposing the death penalty.10. This act presented a new opportunity for inmates, who filed claims in large numbers. The resulting legal congestion, compounded by existing constitutional objections, North Carolina Medical Board’s ethics opinion, and revision of the execution protocol, led to the current moratorium, which is still in effect as of early 2016.

Unlike the post-Furman moratorium, the second moratorium was in part a result of a grassroots movement fighting to abolish capital punishment, whose efforts resulted in thepassage of the RJA. Groups like the North Carolina Coalition for a Moratorium held campaignsto temporarily suspend the death penalty because they wished to eliminate the “arbitrariness, racial disparities, hidden evidence, and classist approach” of the death penalty.11 although thelegal factors directly led to the de facto moratorium in North Carolina, growing opposition to the death penalty played a role as well.

2009 picture of the Sojourners for Abolition and Reconciliation marching against the death penalty. Credit: Photographer: Anthony Shepherd

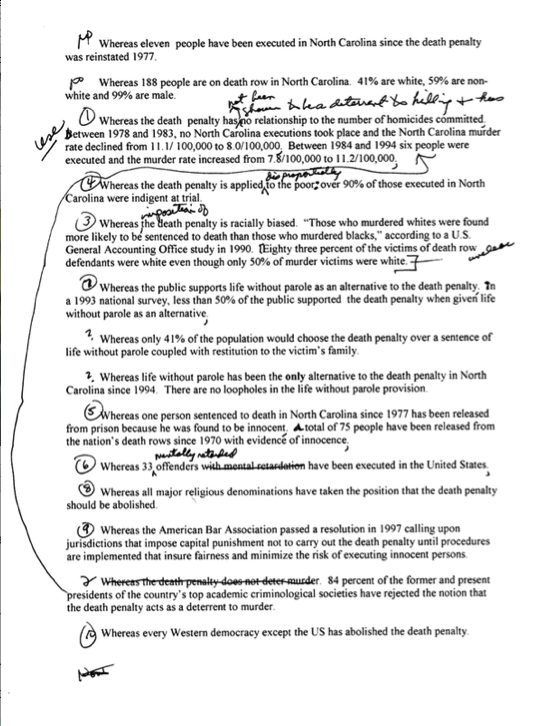

The draft of Ellie Kinnaird’s bill which first proposed a moratorium on the death penalty (courtesy of University ofNorth Carolina at Chapel Hill Southern Historical Collection)