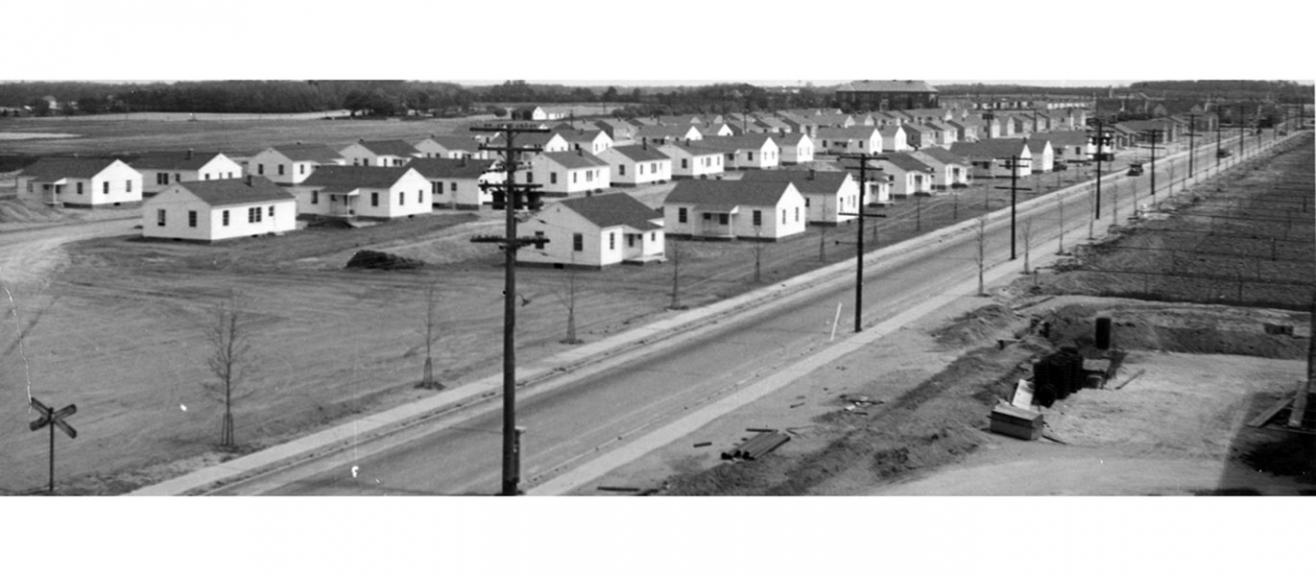

The West Village of Seabrook Farms; built in 1946 and made up of prefabricated bungalows. Courtesy of: Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center, Rutgers University Community Repository Collection

Architecture is the stage upon which our lives play out and, whether we are aware of it or not, these built environments help shape our sense of self. The physical elements of the architectural fabric set an emotional tone for both buildings and those who occupy these spaces. The ability of architecture and planning to construct the identities of its inhabitants, however subconsciously, is worth noting, especially in the context of incarceration.

Prison architecture intentionally imparts a sense of physical, social, and psychological control upon its inhabitants. Traditional images of prisons bring to mind thick, imposing masonry, dull monochrome coloring, and restrictive metal bars. According to ideologies developed during the nineteenth century, prison architecture serves to isolate and at times sensually deprive inmates, while also exerting messages of dominance and constant surveillance, real or imagined, upon those who inhabit these spaces.

Though not a prison in the traditional sense, the architecture at Seabrook Farms also imposed a degree of control over its inhabitants. Laborers procured from racialized groups in crisis, such as those from Japanese Internment Camps, German POWs, Southern migrants, and various European and South American refugees, were housed in mass-produced structures situated within the well-controlled sphere of the Seabrook Farms agri-complex. Domestic settings at Seabrook were segregated by gender, nationality, race, and marital status; this served to regulate and restrict the social interaction of the population to a certain degree.

The residents of Seabrook Farms were not inmates, and had the freedom to leave if they desired – even if it was only to go to another work release site that had been approved to accept Japanese American and immigrant detainees. However, many opted to stay within the ghettoized architectural environment of Seabrook because of the larger threats of segregation and prejudice posed by the outside world; so, the restricted movements of Seabrook residents was partly self-imposed. As a result of this voluntary isolation, a vibrant, rich, diverse cultural community took root at a farm in southern New Jersey.

To visit the online exhibit and learn more about this history, please go to: www.njdigitalhighway.org/exhibits/seabrook_farms