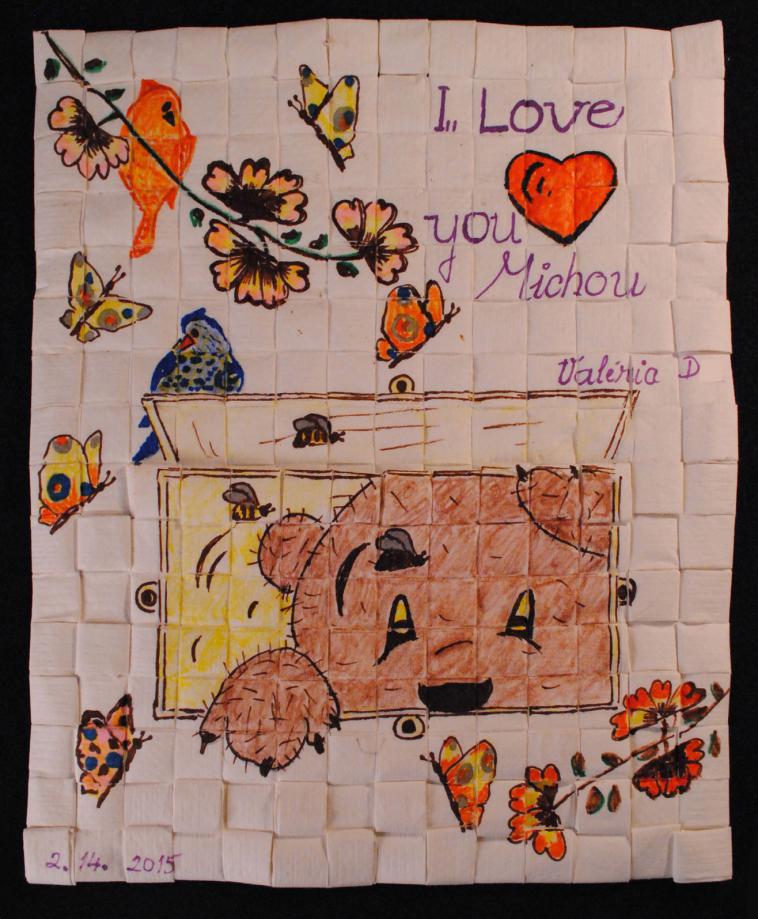

Paper towel canvas made by a woman who brought to First Friends upon her release. Credit: Photograph by Erin Donnelly and Kristyn Scorsone

“Unless we do radical kinds of recovery work around archives, and also grapple with profoundly absent archives—by acknowledging missing lives and missing feelings—we can't move forward.” - Ann Cvetkovich

One of the biggest challenges we faced early on in our project was how to look at and present the artwork. Was it, in fact, art or were we using our authority and privilege to make the objects into art? How can we talk about the pieces when we had no knowledge of who created them? What would happen to the work once we photographed it? How could we tell a story about the work that honored and respected the detainees who created them? We were faced with many questions to which the answers seemed out of reach.

Since we had so little information about the detainees who had created the work and no viable way to get in touch with them, we began to think about genre as a starting point for understanding the work. There are many ways that the detainee artwork may be perceived. The pieces could be viewed as art therapy, outsider art, folk art, or not as art at all. We chose to think about the artwork as outsider art. In the book Outsider Art: From the Margins to the Marketplace, David MacLagan defines outsider art as “extraordinary works created by people who are in some way on the margins of society, and who, for whatever mixture of reasons, find themselves unable to fit into the conventional requirements – social and psychological, as well as artistic – of the culture they inhabit.” Outsider art is produced by people who are untrained as artists and are not created with the concern of commercial promotion. Outsider art can (and often does), however, possess a certain intentionality and these collections are often private and exist under the radar.