Societal, cultural, and religious conceptions of the body and soul, and their roles in facilitating the human experience, have informed the exercise of captivity in societies throughout history. By examining carceral structures in medieval European Christianity and in the Mexica Empire, we can better understand how societal and religious views of the body and the soul are inextricably linked to the manifestation of carceral structures in society.

Conceptions of the body, the soul, and their importance to the individual informed the development of carceral structures in medieval Christianity. As canon and monastic law developed, so did the purpose of incarceration and confinement: by restricting the body, the prison became a conduit to spiritual transcendence and salvation. In this period, the prison became the site of healing for the soul, oftentimes being located directly next to the monastery infirmary.

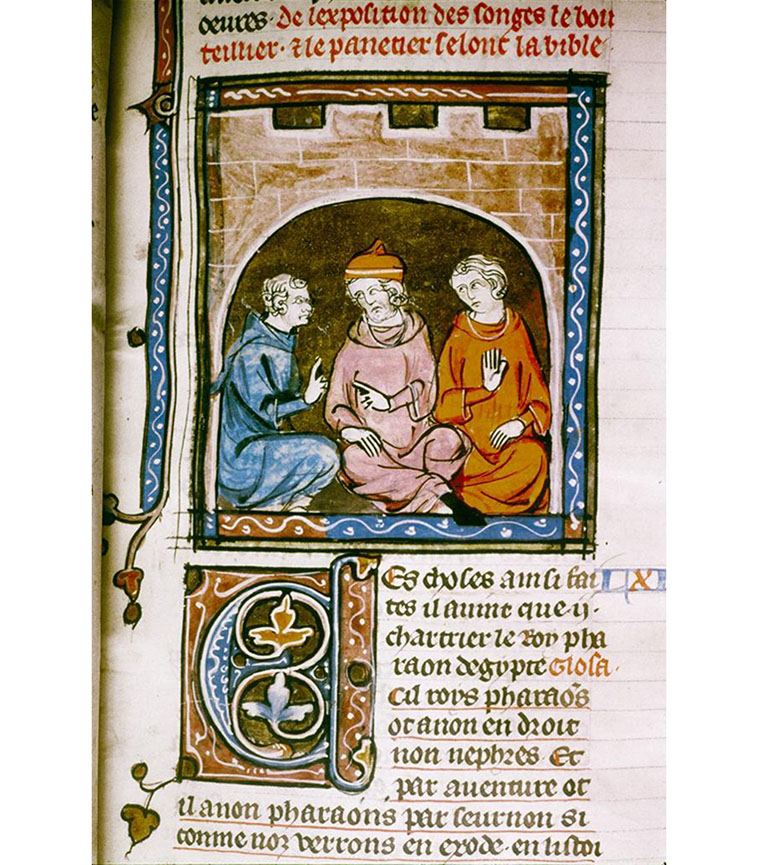

Joseph, in prison, explains the dreams of Pharaoh's chief butler and baker. Credit: Bible Historiale by Guyart Desmoulins, early 14th century Courtesy of: The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

We can trace the widespread use of prison as a site of heightened spirituality to the Biblical narratives of Joseph and Jesus Christ, early Christian martyrs who resisted denouncing their faith. In Joseph’s prison narrative, he can foresee the future by interpreting dreams of the Cupbearer and Baker, making carceral settings holy and spiritual places (Genesis 40: 6-23). Further, Jesus’ captivity narrative in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem plays a similar role in setting a precedent in Christianity for the prison as a conduit to a higher spiritual existence.

By the Middle Ages in Europe, we see the rise of the prison through texts like Aelred de Rievalux’s 12th Century “Rule of Life for a Recluse,” which outlines best practices for spiritual confinement. For many like Aelred, confinement of the body in prison is not enough to reach spiritual clarity—he writes that in confinement, “the mind roams at random, grows dissolute and distracted by cares, disquieted by impure desires.”1 While the prison is the first step to reach this spiritual clarity, Aelred writes that the physicality of the prison must be accompanied by internal barriers set up by an individual to attain piety, including refusing human contact from others and denying oneself the ability to speak.2 For Aelred and many other early Christians, the self-imposed restriction of the exterior self is the path to achieve the “opportunity of advancing to greater perfection” of the soul.3

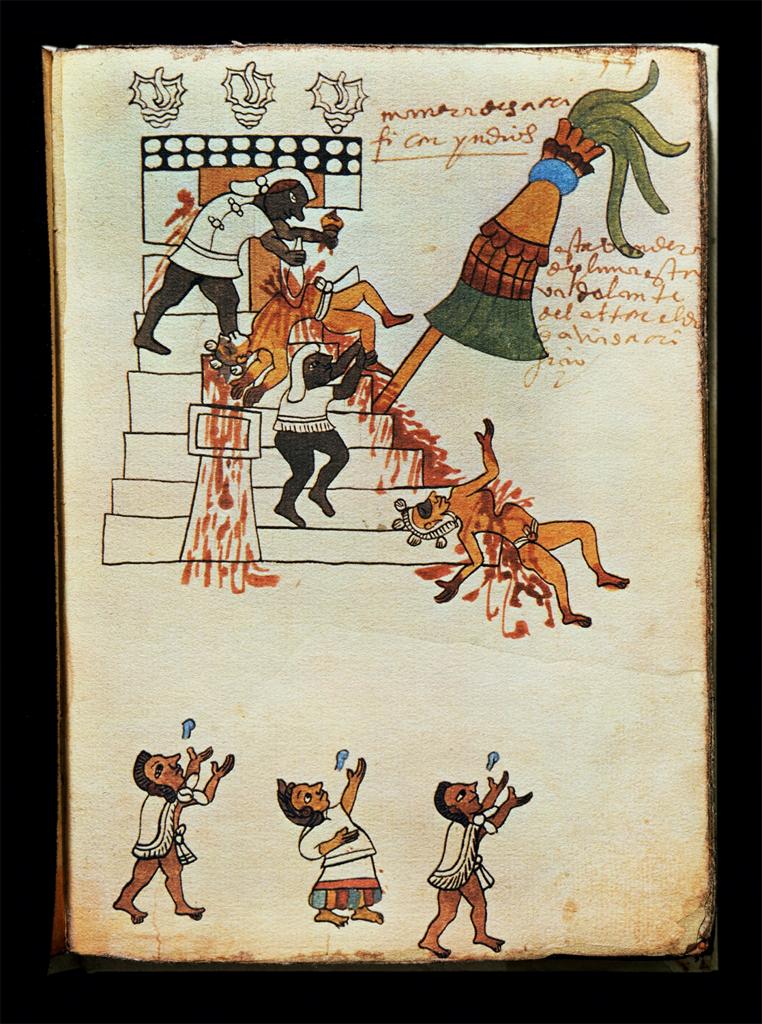

Aztec human sacrifice, 16th century watercolor. Courtesy of: Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

Warfare was to take captives and rip out their beating hearts as a religious ceremony. While this punishment is inflicted on the body, the motivations for such punishment is spiritualized. The sacrificial spilling of blood was thought to be necessary to sustain the cosmos, leading to more rainfall and more crops. In short, for the Mexicas, physical punishment was spiritually necessary to attain physical sustenance, demonstrating a clear connection between body and soul.

The indelible connection between the body and soul is also apparent in the Mexica Empire’s captor and captive relationships: in order to elevate the collective souls of the Mexica people, it was imperative to restrict and sacrifice the bodies of captives. The Flowery Wars were mutually agreed upon battles, with the intention of generating more captives during times of crop failure and drought. Battles would be arranged between two warriors of equal rank—when the captor defeated the captive, he would remove and then wear the skin of the captive as a symbol of their connection and sameness. Then the captor would bring the meat of the defeated captive home to be eaten by his family. The captor would not consume any of the captive because this would be considered self mutilation or eating himself. The captor and captive are viewed as mirror images of each other. While this carceral structure is clearly a violent punishment to the body, the target is the soul and expressions of spiritual gratitude. The most honorable death to ensure that one’s soul had a space in heaven was a death at battle or in a Flowery War.

Throughout history, the body and the soul have both played key roles in the dialogue and ideology bolstering carceral structures. How prison and captivity have manifested is informed by guiding societal ideologies on the role and purpose of the body and the soul in the human existence.

Footnotes

1 Aelred de Rievaulx, “Rule of Life for a Recluse” (1158-1160), 45-46.

2 Ibid, 54-55.

3 Ibid, 61.