Pathways to Death Row: Systemic, Historical, and Individual Perspectives

In the fall of 2015, our class at Duke University explored the death penalty in North Carolina, in particular the driving forces behind the current system of capital punishment. Thus, a defining question quickly emerged: what pathways bring someone to death row? We ultimately uncovered three layers here: First, systemic pathways, or inequalities in the system reflect current societal issues. Second, historical pathways illustrate correlations between past extrajudicial executions and today’s state executions. Finally, individual pathways bringing specific inmates to death row today show the nuance in these trends and give voice to an often-silenced population.

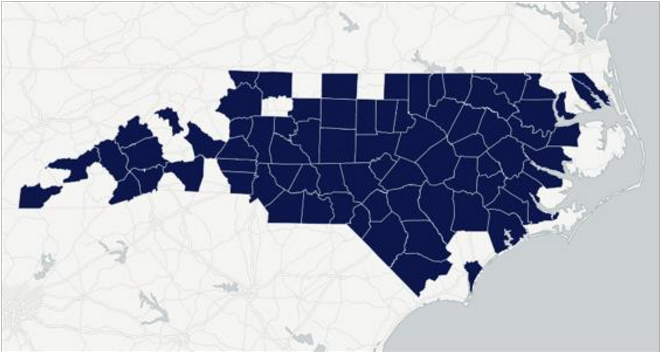

Map of North Carolina that highlights in blue the counties that have disproportionatelysentenced black individuals to death since 1910. Of the 11 counties not highlighted, 5 havenever sent an inmate to death row. Courtesy of: Duke University

Capital punishment often reinforces and reproduces social inequalities that remain unaddressed by the criminal justice system. The map above highlights counties in North Carolina that have sentenced blacks to death disproportionately to black population percentages since 1910. Almost every county is highlighted. For decades, activists, inmates, and scholars have argued that the social, political, and economic power dynamics of society are reflected in prisons, especially in the marginalization and oppression of blacks today. This map shows how these racialized dynamics play out on North Carolina’s death row and how systemic social inequalities have affected the state’s use of legal execution.

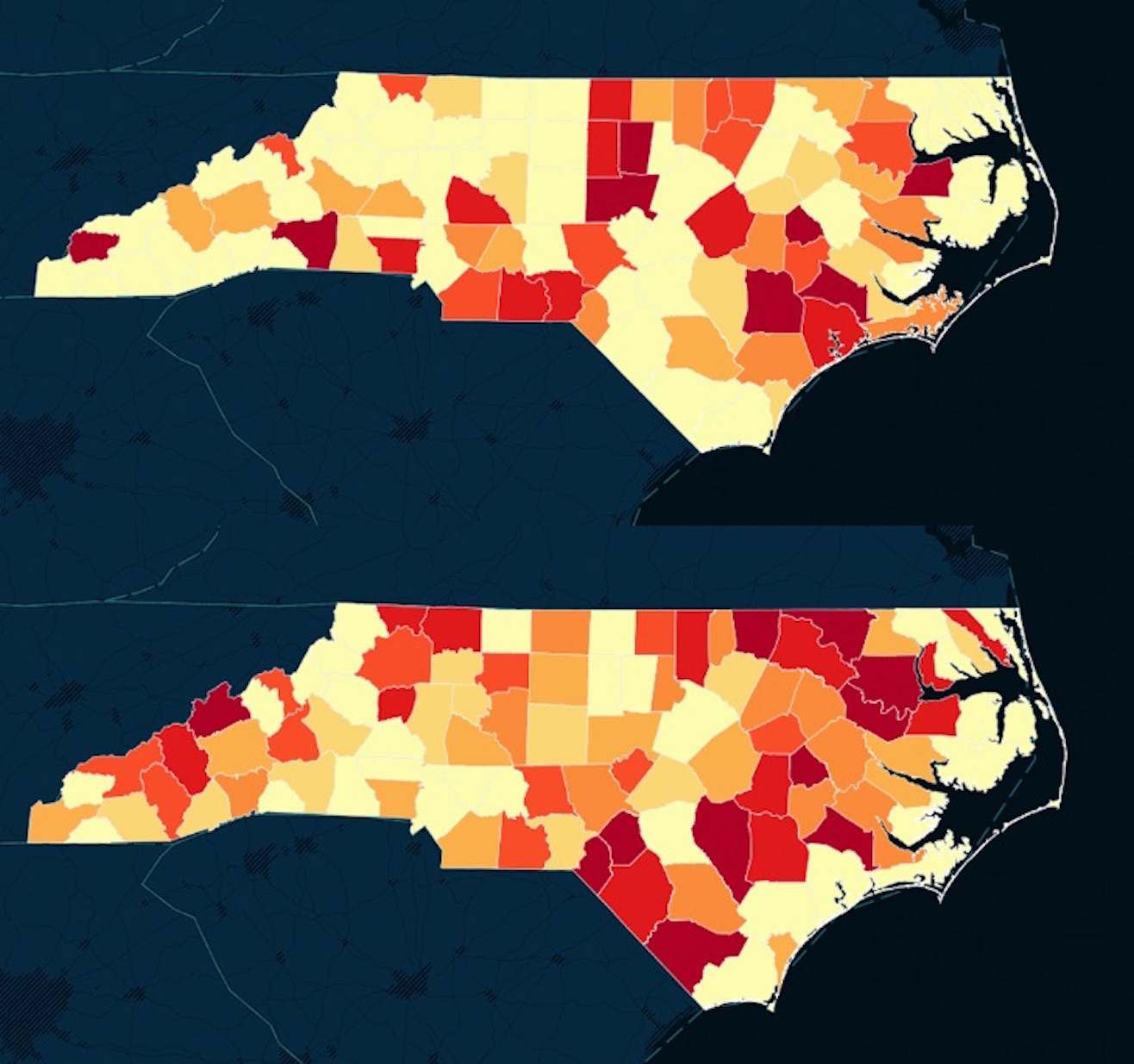

Above: lynchings per capita in each North Carolina county (data retrieved from the Locating Lynching Map created by The University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Introduction to Digital Humanities course). Courtesy of: Carly Meyerson and Safiya Driskell

This contemporary social and political climate of the death penalty reflects the historical pathways to today’s system of capital punishment as well. In some ways, like with execution methods, the death penalty in North Carolina has evolved since the state assumed responsibility for executions in 1910. In less tangible ways, however, the death penalty still reproduces centuries-old social inequalities. The map above compares the number of lynchings per capita to the number of executions per capita in each North Carolina county, demonstrating the ways in which today’s death penalty is built on the foundation of these extrajudicial killings. Many of the counties that lynched the most blacks in the decades following slavery now execute the highest number of inmates in the state, inmates who are predominantly black. For example, Alleghany and Duplin show high numbers of both lynchings and executions. In addition, both lynching and capital punishment tend to punish crimes involving white victims more harshly than those with black victims. Thus, the racial demographics of death row inmate individuals reflect systemic racism or at the very least deep prejudice, and authors such as Dylan Rodriguez have traced this historical pathway of segregation back to slavery in the U.S.

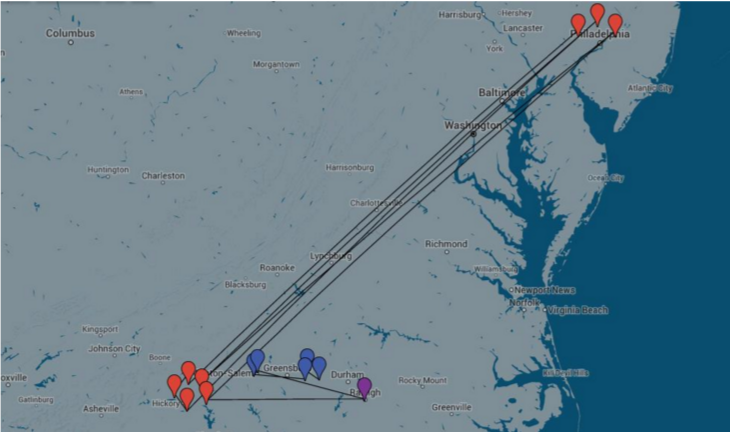

Bowie’s and Moore’s path, in red and blue respectively, were drastically different, converging at Central Prison’s death row. Courtesy of: Duke University

While these historical and systemic pathways show general trends in the carceral state,the individual pathways that bring inmates to death row are all radically different and often ignored, creating a voiceless subset of the population. The comparison of two inmates currently on death row illustrate these variations. Nathan Bowie was 22 when he was convicted of a murder that occurred while visiting family in North Carolina. He fled to Philadelphia, but returned to turn himself in for the crime. A comprehensive view of Bowie’s case shows an unstable childhood in housing projects and group homes, character witness testimony of his good nature, and inadequate counsel from an alcoholic public defender. Blanche Moore also currently resides on death row, convicted of murdering her husband and suspected of killing at least four more men. Moore premeditatively killed multiple victims and exhibited no remorse, according to witnesses, jurors, and investigators. In fact, Moore spent the time before her arrest attempting to collect on her husband’s will. Moore still maintains her innocence, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Ultimately, the system of capital punishment does not differentiate between Bowie and Moore. Convicted of the same crime, the two share the same space on death row today. The above map physically represents the fact that Bowie and Moore’s paths pre-conviction were drastically different, but they ultimately converge permanently at Central Prison’s death row because the state considered them both deserving of execution. The stories of the other 146 current inmates on death row in Raleigh are equally diverse and complex, yet they all converge on death row. With this complexity in mind, who, then, is a criminal deserving to die? Are personal pathways reflected in death sentences? Is it possible to create a system of capital punishment that fairly respects the historic and contemporary pathways that lead to injustice and prejudice in the justice system and represents the circumstances of a crime, a victim, and its perpetrator?

Works Cited:

Rodriguez, Dylan. “(Non)Scenes of Captivity: The Common Sense of Punishment and Death.”

Radical History Review, no. 96 (2006): 9-32.Schutze, Jim. Preacher’s Girl: The Life and Crimes of Blanche Taylor Moore. Morrow Publishing: New York, 1993.