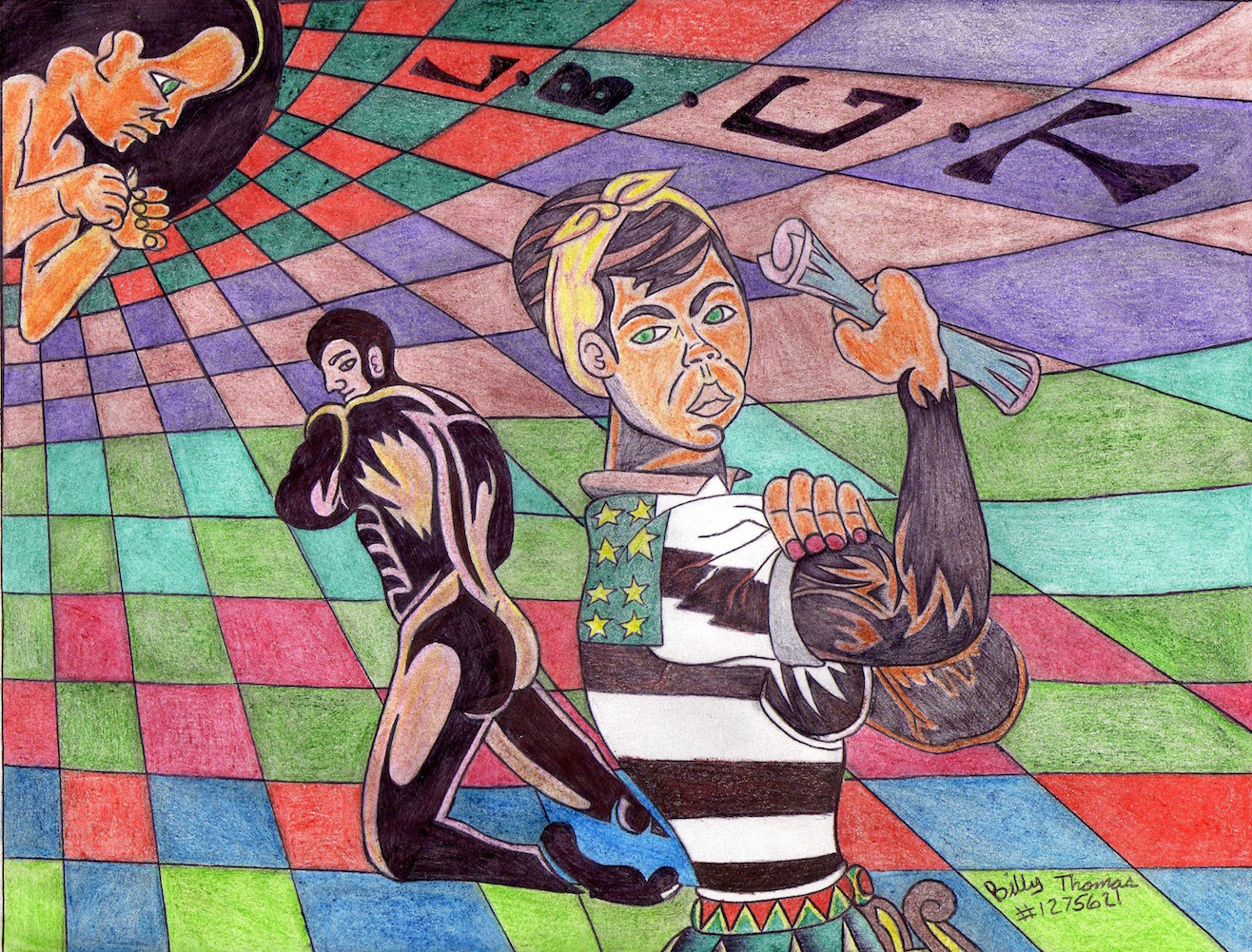

Black and Pink, a prison abolitionist organization, serves LGBTQ prisoners through advocacy, education, and organizing. Courtesy of: Billy Thomas, artist, Black & Pink

Punitive policies and practices have been critical to the growth of mass incarceration. In the case of sexual violence, however, imprisonment functions as a substitute for substantive and transformative social change. Rather than provide long-term solutions to social ills, mass incarceration (and the extensive systems of surveillance that accompany it) has become a catch-all solution for containing society’s undesirables and a quick way for policymakers to gain political capital, despite evidence that punitive measures do not keep communities safe from sexual violence. In an effort to monitor and make accountable sexual predators, sex offender registries became widespread across the United States in the 1990s. Yet the increased state surveillance of sex offenders does not necessarily protect people from sexual and gender-based violence. Besides the reality that sex offenses cover a range of acts varying widely in severity, sex offender registries also have weak links when it comes to preventing recidivism, and may actually contribute to increased risks of reoffending. Moreover, such registries perpetuate myths about the prevalence of stranger rape – in actuality, one’s family members, friends, and acquaintances are the most likely to perpetrate acts of sexual abuse and violence.

This continued surveillance and other forms of state control serve as poor placeholders for addressing sexual and gender-based violence in meaningful ways, while simultaneously obscuring the ways in which the state perpetuates sexual violence in prisons. In the U.S. there is a general acceptance of brutal sexual violence in prisons as inevitable, and no meaningful policy change has sought to ameliorate the sexual abuse of incarcerated individuals. The ways in which prisons facilitate sexual assault alone should cast doubt on the ability of the carceral state to address sexual violence. Clearly, incarceration is no solution to sexual assault: as legal activist and author Alexandra Brodsky writes for Feministing.com, “It is unconscionable that the criminal justice system demands that survivors either remain silent or condemn their assailants to the same violence they have suffered.” The relationship between sexual violence and incarceration on women of color (especially LGBT women of color) is even more astounding. Sexual abuse is one of the most significant predictors of the incarceration of girls (who are disproportionately nonwhite and LGBT), in what has been termed by the Human Rights Project for Girls the “sexual abuse to prison pipeline.” Punitive and far-reaching penal policies form a veneer of safety from sexual violence that serves to objectify and commodify the bodies of survivors who already experience “institutional, administrative, structural, private and state violence.” Rather than prioritizing the needs of survivors, forces that are otherwise apathetic towards (if not actively perpetuating) sexual trauma work to expand the reach of the carceral state in the name of combating sexual violence. If our aim is to address sexual violence in a meaningful manner, we must go beyond the “conservative victims’ rights movement premised on a zero-sum vision of justice that pit[s] victims against offenders” and replace the punitive realities of the carceral state with possibilities for community accountability and imaginative, transformative forms of justice.

1 Marie Gottschalk, Caught: The Prison State and the Lockdown on American Politics, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 211: “Registration, community notification, and residency restrictions may actually increase recidivism rates by contributing to social isolation, unemployment, residential instability, depression, harassment, and feelings of shame, fear, and hopelessness, all of which are factors associated with a greater risk for reoffending.”

2 Ibid., 213-214. See also, Human Rights Watch, "U.S. Sex Offender Laws May Do More Harm Than Good," September 7, 2007, accessed December 21, 2015,https://www.hrw.org/news/2007/09/11/us-sex-offender-laws-may-do-more-har.... According to Gottschalk, friends, acquaintances, and family members are responsible for over 90% of child sexual abuse, and nearly 90% of all sexual abuse. For additional information, please see the website for the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN).

3 Gottschalk, Caught, 137. The only major piece of federal legislation aimed at addressing sexual violence in prisons, the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), is not legally binding for state prisons or local jails.

4 Alexandra Brodsky, “The Radical Potential and Great Disappointment of School Sexual Misconduct Boards.” Feministing, March 8, 2013, accessed December 2, 2014, http://feministing.com/2013/03/08/the-radical-potential-and-great-disapp.... For additional information about sexual abuse in prisons, consider reading David Kaiser and Lovisa Stannow’s March 2011 article “Prison Rape and the Government” in The New York Review of Books, which can be found here: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2011/03/24/prison-rape-and-government/?p...

5 Reina Gattuso, “How the Justice System Hurts Survivors Through the ‘Sexual Abuse to Prison Pipeline.’” Feministing, August 7, 2015, accessed December 2, 2015, http://feministing.com/2015/07/14/how-the-justice-system-hurts-survivors.... The full report, drafted by the Human Rights Project for Girls, can be found here: http://rights4girls.org/wp-content/uploads/r4g/2015/02/2015_COP_sexual-a...

6 Incarceration to Education Coalition, “Abolish the Box: Moving Beyond Criminality in Addressing Sexual Violence.” Crunk Feminist Collective, October 2, 2014, accessed December 2, 2015, http://www.crunkfeministcollective.com/2014/10/02/abolish-the-box-moving...

7 Gottschalk, Caught, 266, and Incite!, “Community Accountability,” accessed December 2, 2015, http://incite-national.org/page/community-accountability.