Blog

The Changing Tide in the Re-Enfranchisement of Felons

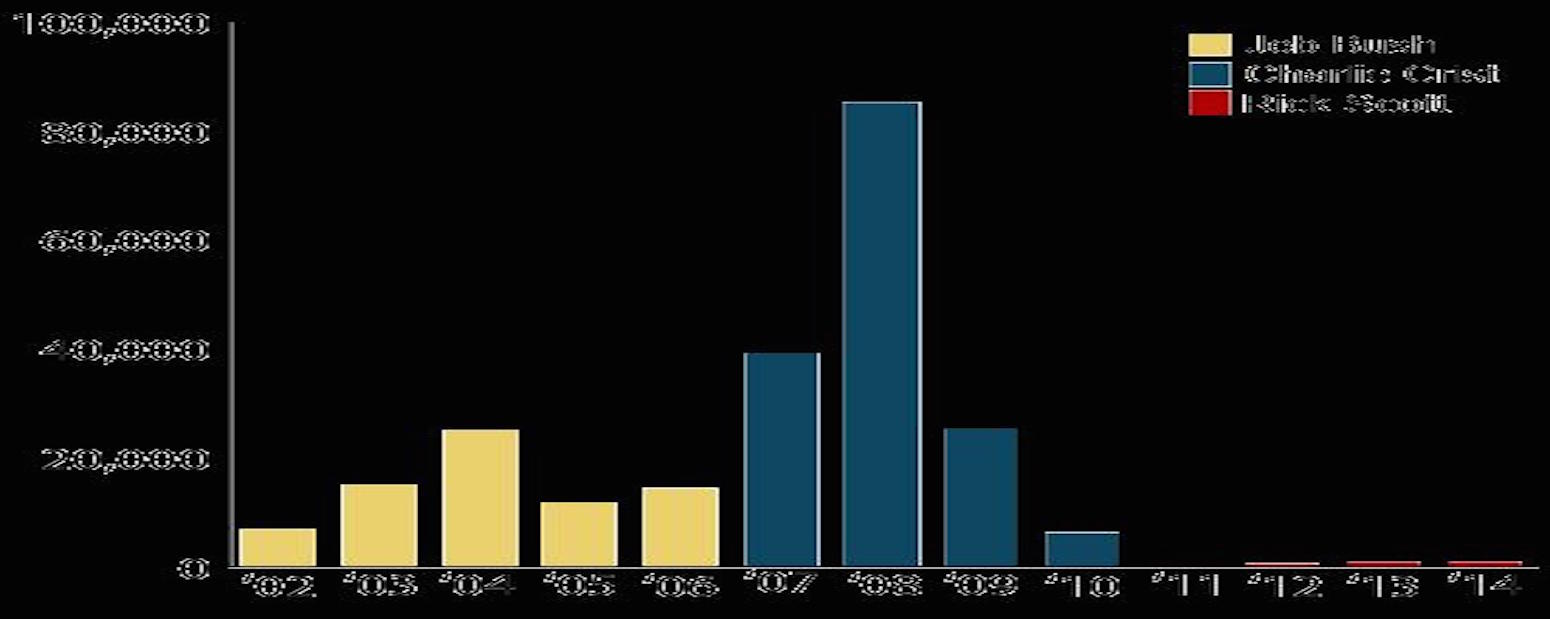

Convicted felons granted voting rights under Governors Jeb Bush, Charlie Crist, and Rick Scott. Courtesy of: Florida Commission on Offender Review

After being convicted of a felony, individuals lose many rights of citizenship, including the right to vote; the right to sit on a jury; the right to possess firearms; the ability to travel abroad to some countries; certain employment opportunities; access to food stamps, public housing, and other social services; and often parental benefits. Felons are paradoxically rightless citizens in that they are beholden to the nation, but cannot enjoy the benefits.

After Kentucky Governor Steven L. Beshear ordered the automatic re-enfranchisement of ex-felons in November 2015, only Iowa and Florida permanently ban all persons with felony convictions from voting. While some states restore rights immediately following release from prison, most require convicts to complete parole and probation before restoring rights. Only Vermont and Maine do not disenfranchise any people with criminal convictions at any point. Release from prison implies the person’s ability to assimilate back into society following his or her rehabilitation. Refusing their right to vote, a basic responsibility of citizenship and foundation of democracy, negates the trust given to that person by society.

The ACLU provides an interactive map on its website that shows voting rights of felons in each state across the country. According to this map, most states have laws that do not allow people in prison, on parole or probation to vote, but they can vote upon the completion of their sentence.

Between 2007 and 2011, Democratic Florida Governor Charlie Crist automatically restored voting rights to over 155,000 nonviolent offenders who finished sentences. When Republican Governor Rick Scott assumed office in 2011, he halted the restoration of rights. Just over 1,500 felons have received their rights to vote under individual review. Ironically, in 1997, the company Scott co-founded admitted to fourteen felonies in the largest fraud settlement in US history, although Scott was not personally charged.

During his term as Democratic Governor of Iowa between 1999 and 2007, Tom Vilsack enacted a six-year policy to automatically give felons their voting rights after ending sentences, parole and probation. On the day he took office, the new Republican Governor Terry Branstad signed an order to reverse the policy, making Iowa one of the strictest states in terms of felons’ voting rights. This was wildly different from the national trend. Under his policy, former felons have to apply to him, including their credit report, a requirement unique among states. Between 2007 and 2012, 8,000 felons completed all state supervision, and only a dozen received voting rights.

Unlike many current issues, re-enfranchisement has gained bipartisan support, as evidenced by the overwhelming number of states, regardless of political affiliation, that allow for re-enfranchisement. Both sides seem to understand that the re-entry process of prisoners into society needs improvement. Upon release from prison, individuals face major personal and legal adjustments to life after time served. Requiring them to jump through innumerable, and oftentimes impossible, hoops to vote is often a deterrent in reacquiring the right to vote. When Henry Straight, a former felon in Iowa, attempted to regain his voting rights to serve on his town council, even his lawyer could not file the paperwork properly – Straight was rejected. This is bad public policy. Re-enfranchising rehabilitated former felons is the first step in helping large groups of marginalized people re-assimilate into their nation and communities.