Blog

Carceral Power and the Geography of Incarceration in Massachusetts: Pt. 2

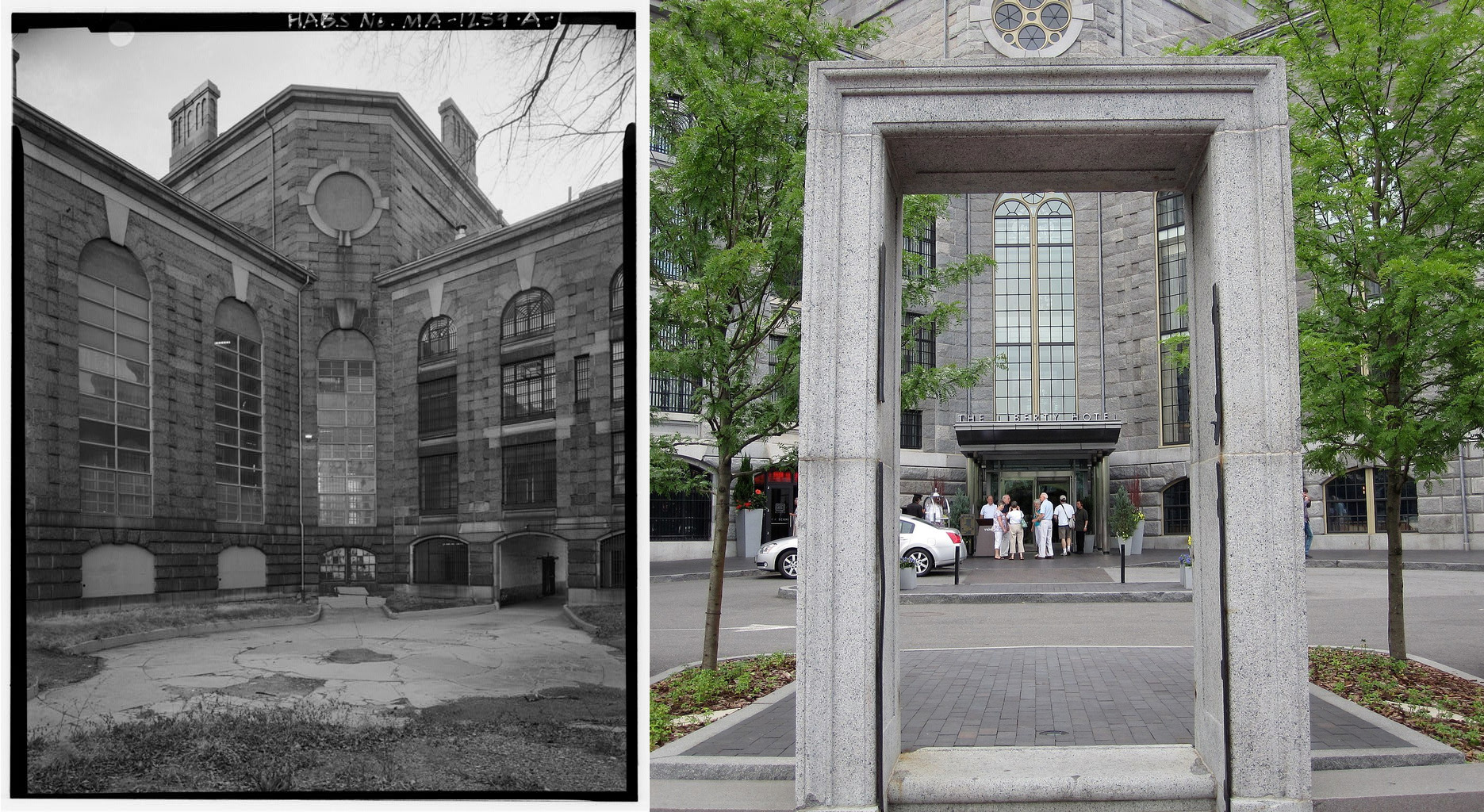

The Charles Street Jail, which was transformed into the Liberty Hotel (pictured on right).

Editor's Note: This is part two of a two-part blog about the contributions of Northeastern public history students to the local States of Incarceration exhibition in Boston. Read part one here.

One of Northeastern's local panels, produced by public history graduate student Kara Zelasko, looked at the intersection of past and present through the historic preservation of the former Charles Street Jail. While the jail retains much of its original appearance, it now serves the public in a very different context.

The Charles Street Jail finally closed its doors in 1973 after decades of overcrowding and dilapidated conditions. With a $150 million budget, developers transformed the building into the boutique Liberty Hotel. Guests can drink $18 cocktails where the drunk tank stood, practice yoga in the former prison yard, or dine next to granite cells previously deemed unconstitutional by the US District Court.

Despite its status as a national landmark, the ironically named hotel minimally and selectively engages with its former life as a jail. The small exhibit (housed by the restrooms) and the website emphasize the impressive architecture and centers the narrative on its architects, ignoring the experiences of the people who were held there. The Liberty Hotel is a local example of how history can be at once highlighted, obscured, commodified, and preserved in a single place.

An additional panel on the geography of incarceration in Boston explored the spatial history of the

effect of imprisonment on the city. Some neighborhoods with a high rate of incarceration suffer from a cycle of over-policing, imprisonment, and recidivism. Created as a collaboration between public history graduate student Caroline Klibanoff and criminology graduate student Stacie St. Louis, the panel blended a humanistic perspective with data from the social sciences.

Working with sociologists brought both challenges and benefits to us as public historians. During class discussions, the students in public history tended to focus on the narrative and interpretation of information with an overarching historical lens, highlighting the points we felt seemed most unjust or disturbing, and which would be most relevant or most important for exhibit visitors. Criminology students, already deeply familiar with the literature and statistics on incarceration, helped anchor the discussion with contemporary facts and figures on incarceration today.

After some time spent adjusting to each others’ points of view, we were able to work together to make the exhibit stronger in its telling of both historic and contemporary issues of incarceration. The breadth of perspective involved in creating this exhibit and these panels improved its content and delivery – and gave us a valuable collaborative experience in the process.