Blog

Carceral Power and the Geography of Incarceration in Massachusetts

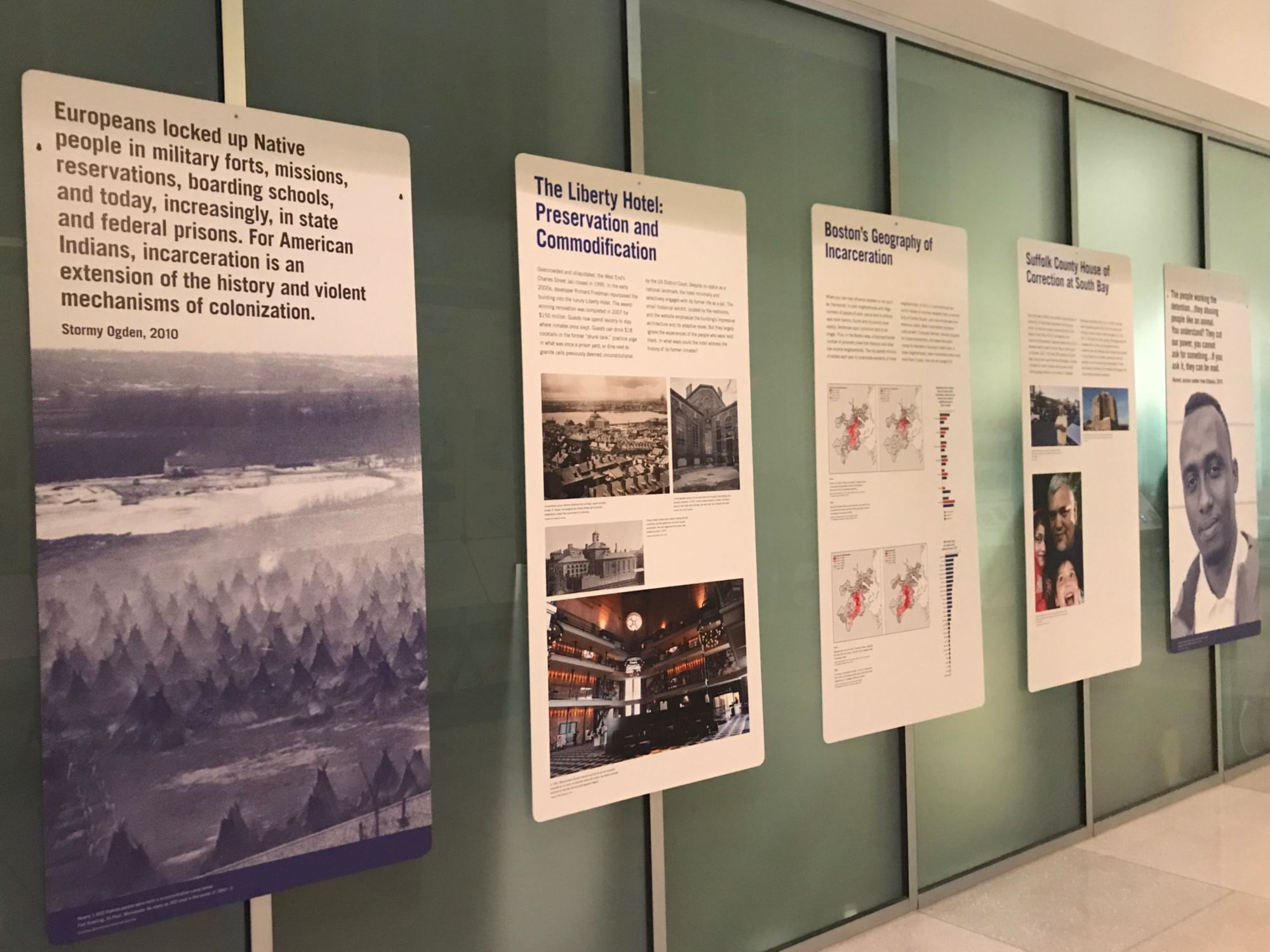

Local exhibit panels produced by public history graduate students at Northeastern University.

Editor's Note: This is part one of a two-part blog about the contributions of Northeastern public history students to the local States of Incarceration exhibition in Boston.

In 2016, Northeastern University public history graduate students contributed a panel about the Norfolk Prison Debate Society to the traveling States of Incarceration exhibit. When the exhibit was on display at Northeastern in 2018, it featured six additional panels focusing on Boston’s local history of incarceration produced by a different cohort of graduate students in a Public History of Incarceration seminar taught by Dr. Martin Blatt.

These panels looked at historical examples of incarceration at Deer Island, Charles Street Jail, Dorthea Dix’s activism, and Malcolm X’s Boston in addition to contemporary examples of carceral power with the geography of incarceration and the Suffolk County House of Correction. The exhibit opening coincided with a symposium on mass incarceration hosted by Northeastern that featured perspectives from historians, criminologists, and community advocates. The collaboration to bring this exhibit to Northeastern spanned cohorts and disciplines, which allowed for a deep exploration of the memory and current reality of incarceration in Boston.

Most of the local panels we created explored the connection between memory and place: the adaptive reuse of the Charles Street Jail, the Boston imprisonment of "Detroit Red" Little (Malcolm X), the multiple incarnations of incarceration that took place at Deer Island, or the over-policing of certain neighborhoods today. Some of these sites were explicit places of carceral confinement while others deepen our recognition of the layers and strands connected to the history of incarceration in Boston. In any instance, these places are almost unrecognizable today as sites connected to the carceral state: the Liberty Hotel glosses over the brutal conditions inmates endured with a swanky interior, Malcolm X’s activity in Detroit and New York City overshadows the formative years Malcolm Little spent in Boston, Deer Island operates as a wastewater treatment plant, and policing patterns change as neighborhoods do.

The current reality and historical memory of incarceration in Boston loomed large in our local panels, but seems widely unaddressed in the physical spaces touched by incarceration today. When the exhibit opened on Northeastern’s campus, it was hard to ignore the fact that these panels faced the Boston Police Headquarters in the Roxbury neighborhood, on a street that intersects with Malcolm X Boulevard. It’s this intersection of history, memory, and place that allows us to begin to understand the nuances of Boston’s relationship with incarceration.